By William Schomberg and Balazs Koranyi

LONDON/FRANKFURT (Reuters) – This time last year, the world’s biggest central banks were united in getting the inflation story wrong.

Now, as top policymakers gather for the Kansas City Federal Reserve’s annual monetary policy conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, the U.S. central bank looks like it might manage a “soft landing” for its own economy, but the outlook for Europe is far more worrying.

Much of the world is facing the fastest price growth since the early 1980s, raising fears of a repeat of that era’s wage-price spiral phenomenon that required double-digit interest rates – and painful recessions – to restore price stability.

That leaves many of the central bankers heading to the Grand Teton mountains this week hoping today’s inflation pressures will abate quickly enough to allow them to counter the downturns anticipated in economies around the world.

“They are caught between a coming recession and sky-high inflation. Their first concern is to react to high inflation,” said Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg. “Once the recession is clearly there, the concern will shift.”

That shift, though, could well be asymmetric, with the Federal Reserve in particular signalling an unwillingness to quickly reverse gears.

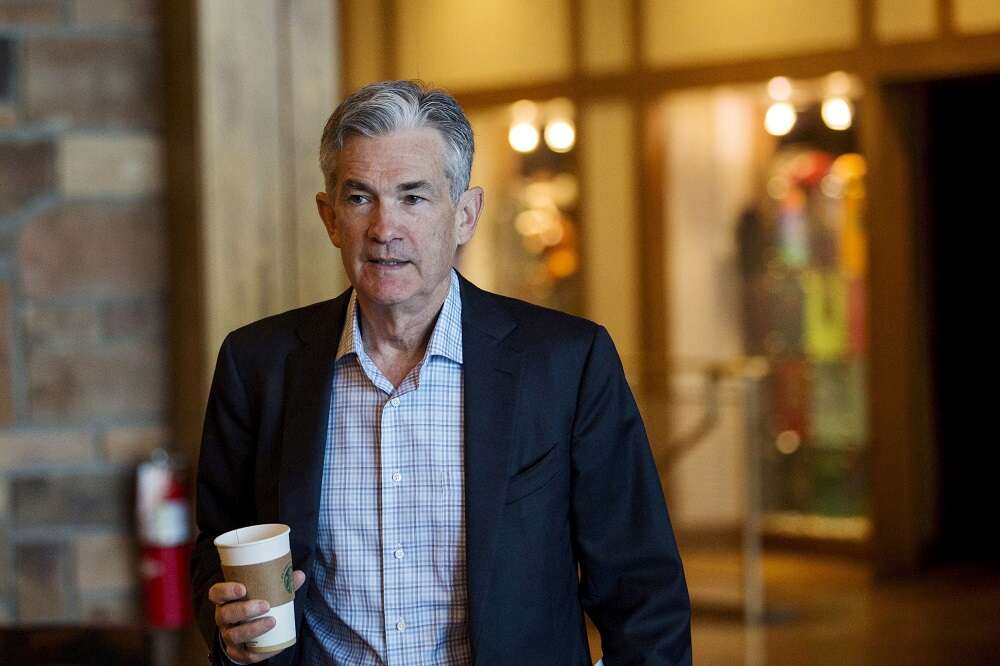

Last year at this time, for instance, Fed Chair Jerome Powell asserted that the jump in inflation would likely be transitory. As that narrative unravelled, he became the driving force behind the fastest pace of U.S. monetary tightening in four decades.

Moreover, he and others at the U.S. central bank have also indicated a willingness to tolerate a measure of contraction in the American economy if that is what is needed to tame inflation.

While there are some indications the Fed may soon dial down its rate hikes from the 75-basis-point pace at its last two policy meetings, Powell may use his keynote speech to the symposium on Friday to cool expectations among investors of cuts to borrowing costs in 2023.

“Powell will likely attempt to stress a slower pace of hikes but also a longer period of time in restrictive territory, taking a little wind out of the sail for the dovish pivot narrative,” said Jack Janasiewicz, lead portfolio strategist at Natixis Investment Managers Solutions.

‘WON’T VANISH QUICKLY’

U.S. consumer price inflation fell but was still at nearly a 40-year high of 8.5% in July – down from 9.1% in the prior month – and is expected to average almost 4% in 2023, according to analysts polled by Reuters.

The outlook is starkly worse in energy-importing Europe where Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to sky-rocketing energy prices that look set to keep on accelerating as Moscow retaliates against European sanctions by restricting gas flows.

Euro zone price growth is now set to hit double digits as measures taken by Germany and other countries to soften the cost-of-living hit for consumers start to expire, the Bundesbank warned this week.

European Central Bank forecasts show euro zone inflation will fall to 3.5% in 2023, but its figures have been steadily revised up and Germany now expects inflation above 6%, suggesting the ECB’s next forecasts in September will go higher.

“These inflationary pressures are likely to be with us for some time,” Isabel Schnabel, an ECB board member who will speak at the Jackson Hole symposium, said in a Reuters interview last week.

“They won’t vanish quickly. Even with the ongoing monetary policy normalisation, it will take some time until inflation gets back to 2%.”

The ECB last month raised interest rates for the first time in 11 years.

In Britain, which has taken fewer measures than most other European countries to protect households from the energy price surge and is also suffering from U.S.-style inflationary heat in the labour market, the situation is even more dramatic.

Analysts at Citi said this week that British inflation will hit 18% in early 2023, its highest rate since 1976, despite the Bank of England having already raised interest rates six times since December.

Although other analysts see a lower peak, that kind of hit to living standards is feeding speculation that British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s successor will have to come up with a fresh round of huge support for households to avert a surge in destitution.

“In the UK, there is this talk about loosening fiscal policy, but you are going to essentially force the BoE to keep tightening,” said Kenneth Broux, head of corporate research, FX and rates at Societe Generale.

But Richard Flynn, managing director at Charles Schwab UK, has detected some early signs of a global shift in the stance of monetary policy from the central banks of Brazil and the Czech Republic – among the first movers in the hiking cycle last year – which have suggested that their rates might have peaked.

“Over the past 20 years, the turn from hikes to cuts has tended to be abrupt rather than gradual, often in response to economic recessions,” Flynn said.

“This year’s symposium may provide an early indication of when the turn from hikes to cuts may occur.”

(Additional reporting by Dhara Ranasinghe in London; Writing by William Schomberg; Editing by Dan Burns and Paul Simao)